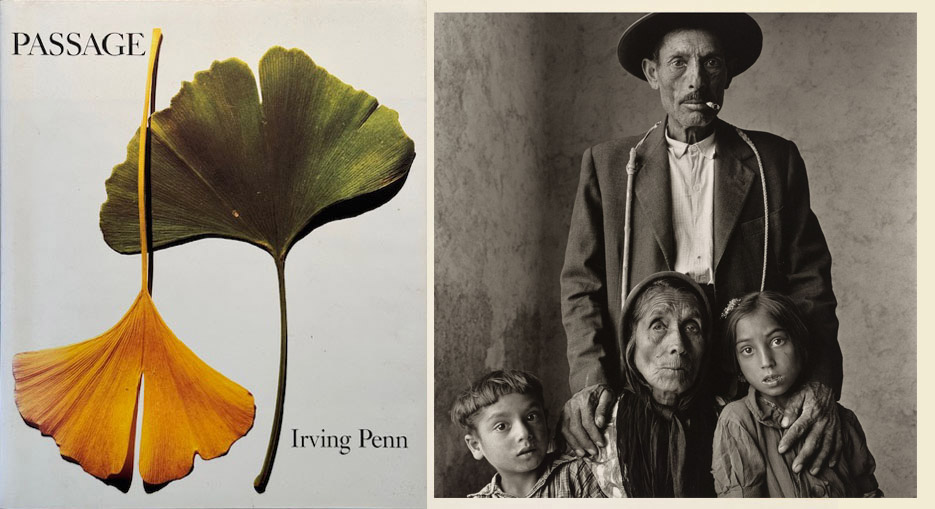

Gypsy Family, Estremadura, Spain, 1965 by Irving Penn, from his book Passage.

They say that photography is a solitary affair and it certainly can be. Sure, there are clubs and organisations you can join for social contact, but when it comes to the actual process of taking a photograph, we're generally wrapped up in ourselves, possibly with our subject if we're shooting portraiture.

So, how did the great photographers think? What was in their minds as they captured their masterpieces? How did they prepare for a shoot? What were they looking for? This is one of the reasons I enjoy reading about other photographers, especially their autobiographical notes. They often share their photo process. And as I get older and gain a little more experience, what I might have read a decade ago and passed over can take on a new relevance today.

And so it was with Irving Penn's book Passage. The takeaway for this blog is that it pays to be passionate about your photography. In the book, Penn talks about landing in a foreign country and hardly being able to contain himself, so strong was his desire to get out into the streets with his camera. When I read this, I instantly related to how I feel when visiting a new location - or when revisiting a location not seen for a long time. I figure most readers feel the same way - there's a built-in enthusiasm to get out into the thick of things.

Why? Because we're passionate about photography - and that's nothing to be apologetic for.

So, why did the photo of the gypsies attract my eye? Look at where Penn has placed the faces: right up the top, down the bottom, there's even one tucked away in the very left hand bottom corner! Talk to any professional portrait photographer and they will generally suggest putting the centre of interest - the face - in the top half of the frame, exactly where Penn has placed the father's white shirt! How would this be judged in a photography competition, not that it matters. It's a Penn masterpiece and all we can do is fathom his approach.

Of course, as you page through Passage, it's hard not to notice Penn's clever use of composition, specifically placing and shaping the subject in all the wrong places and making it work! His approach to portraiture is different, even today. Sure, the gypsies from 50 years ago are full of character, but even if dressed in more contemporary garb, the light, the expressions and the composition would ensure this remained a powerful portrait.

Another takeaway is that Penn really loved natural light, so while many of his most famous photographs are studio lit (where he admits to trying to replicate daylight in some way), he had no trouble looking around for a window with indirect light. How easy it is once you're shown how!